Tom Murphy

A solar panel reaps only a

small portion of its potential due to night, weather, and seasons,

simultaneously introducing intermittency so that large-scale storage is

required to make solar power work at a large scale. A perennial

proposition for surmounting these impediments is that we launch solar

collectors into space—where the sun always shines, clouds are

impossible, and the tilt of the Earth’s axis is irrelevant. On Earth, a

flat panel inclined toward the south averages about 5

full-sun-equivalent hours per day for typical locations, which is about a

factor of five worse than what could be expected in space. More

importantly, the constancy of solar flux in space reduces the need for

storage—especially over seasonal timescales. I love solar power. And I

am connected to the space enterprise. Surely putting the two together

really floats my boat, no? No.

I’ll take a break from writing about behavioral

adaptations and get back to Do the Math roots with an evaluation of

solar power from space and the giant hurdles such a scheme would face.

On balance, I don’t expect to see this technology escape the realm of

fantasy and find a place in our world. The expense and difficulty are

incommensurate with the gains.

How Much Better is Space?

First, let’s understand the ground-based alternative

well enough to know what space buys us. But in comparing ground-based

solar to space-based solar, I will depart from what I think may be the

most practical/economic path for ground-based solar. I do this because

space-based solar adds so much expense and complexity that we gain a

large margin for upping the expense and complexity on the ground as

well.

For example, transmission of power from space-based

solar installations would likely be by microwave link to the ground. If

we’re talking about sending power 36,000 km from geosynchronous orbit, I

presume we would not balk about transporting it a few thousand

kilometers across the surface of the Earth. This allows us to put solar

collectors in hotspots, like the Desert Southwest of the U.S. or

Northern Africa to supply Europe. A flat panel tilted south at latitude

in the Mojave Desert of California would gather an annual average of 6.6

full-sun-equivalent hours per day across the year, varying from 5.2 to

7.4 across the months of the year, according to the NREL redbook study.

Next, surely we would allow our fancy ground-based

panels to articulate and track the sun through the sky. One-axis

tracking about a north-south axis tilted to the site latitude improves

our Mojave site to an annual average of 9.1 hours per day, ranging from

6.3 to 11.2 throughout the year. A step up in complexity, two-axis

tracking moves the yearly average to 9.4 hours per day, ranging from 6.8

to 12.0 hours. We only gain a few percent in going from one to two

axes, because the one-axis tracker is always pointing within 23.5° of

the direction to the sun, and the cosine projection of this angle is

never less than 92%. In other words, it is useful to know that a simple

one-axis tracker does almost as well as a more sophisticated two-axis

tracker. Nonetheless, we will use the full-up two-axis performance

against which to benchmark the space gain.

On a yearly basis, then, getting continuous 24-hour

solar illumination beats the California desert by a factor of 2.6

averaged over the year, ranging from 2.0 in the summer to 3.5 in the

winter. One of my points will be that launching into space is a heck of a

lot of work and expense to gain a factor of three in exposure. It seems

a good bet that it’s cheaper to build three times as many panels and

stick them on the ground. It’s not rocket science.

For technical accuracy, we would also want to correct for the atmosphere, which takes a 21% hit for the energy available to a silicon photovoltaic (PV) on the ground vs. space, using the 1.5 airmass standard.

Even though the 1347 W/m² solar constant in space is 35% larger than

that on the ground, much of the atmospheric absorption is at infrared

wavelengths, where silicon PV is ineffective. But taking the 21% hit

into account, we’ll just put the space gain at a factor of three and

call it close enough.

What follows can apply to straight-up PV panels as

collectors, or to concentrated reflectors so that less photovoltaic

material is used. Once we are comparing to two-axis tracking on the

ground, concentration is on the table.

Orbital Options

Are we indeed dealing with 24 hours of exposure in

space? A common run-of-the mill low-earth-orbit (LEO) satellite orbits

at a height of about 500 km. At this height, the earth-hugging satellite

spends almost half its time blocked from the Sun by the Earth. The

actual number for that altitude is 38% of the time, or 15 hours per day

of sun exposure. It is possible to arrange a nearly polar “sun

synchronous” orbit that rides the sunrise/sunset line on Earth so that

the satellite is always bathed in sunlight, with no eclipsing by Earth.

But any LEO satellite will sweep past the ground at

over 7 km/s, appearing for only 2 minutes above a 30° elevation even for

a direct overhead pass (and only about 6 minutes from horizon to

horizon). What’s worse, this particular satellite in a sun-synchronous

orbit will not frequently generate overhead passes at the same point on

the Earth, which rotates underneath the orbit.

In short, solar installations in LEO could at best

provide intermittent power to any given site—which is the main rationale

for leaving the ground in the first place. Possibly an armada of

smaller installations could zip by, each squirting out energy as it

passes by. But besides being a colossal headache to coordinate, the

sun-synchronous full-sun satellites would necessarily only pass over

sites experiencing sunrise or sunset. You would get all your energy in

two doses per day, which is not a very smooth packaging, and seems to

defeat a primary advantage of space-based solar power in avoiding the

need for storage.

Any serious talk of solar power in space is based on

geosynchronous orbits. The period of a satellite around the Earth can

be computed from Kepler’s Law relating the square of the period, T, to

the cube of the semi-major axis, a: T² = 4p²a³/GM, where GM ˜ 3.98×1014

m³/s² is Newton’s gravitational constant times the mass of the Earth.

For a 500 km-high orbit (a ˜ 6878 km), we get a 94 minute period. The

period becomes 86400 seconds (24 hours) at a ˜ 42.2 thousand kilometers,

or about 6.6 Earth radii. For a standard-sized Earth globe, this is

about a meter from the center of the globe, if you want to visualize the

geometry.

A geosynchronous satellite indeed orbits the Earth,

but the Earth rotates underneath it at like rate, so that a given

location on Earth always has a sight-line to the satellite, which seems

to hover in the sky near the celestial equator. It is for this reason

that satellite receivers are often seen tilted to the south (in the

northern hemisphere) to point at the perched platform.

Being so far from the Earth, the satellite rarely

enters eclipse. When it does, the duration will be something like 70

minutes. But this only happens once per day during periods when the Sun

is near the equatorial plane, within about ±22 days of the equinox,

twice per year. In sum, we can expect shading about 0.7% of the time.

Not too bad.

Power Transmission

Now here’s the tricky part. Getting the power back

to the ground is non-trivial. We are accustomed to using copper wire for

power transmission. For the space-Earth interconnect, we must resort to

electromagnetic means. Most discussions of electromagnetic power

transmission centers on lasers or microwaves. I’ll immediately dismiss

lasers as impractical for this purpose, because clouds block

transmission, because converting the power into electricity is not as

direct/efficient as it can be for microwaves, and because generation of

laser power tends to be inefficient (my laser pointer is about 2%, for

instance, though one can do far better).

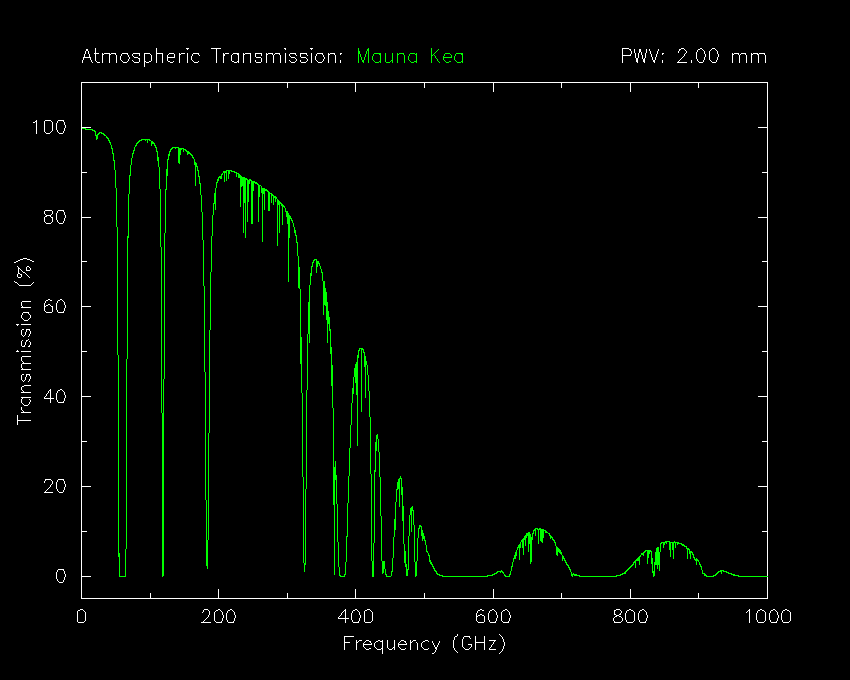

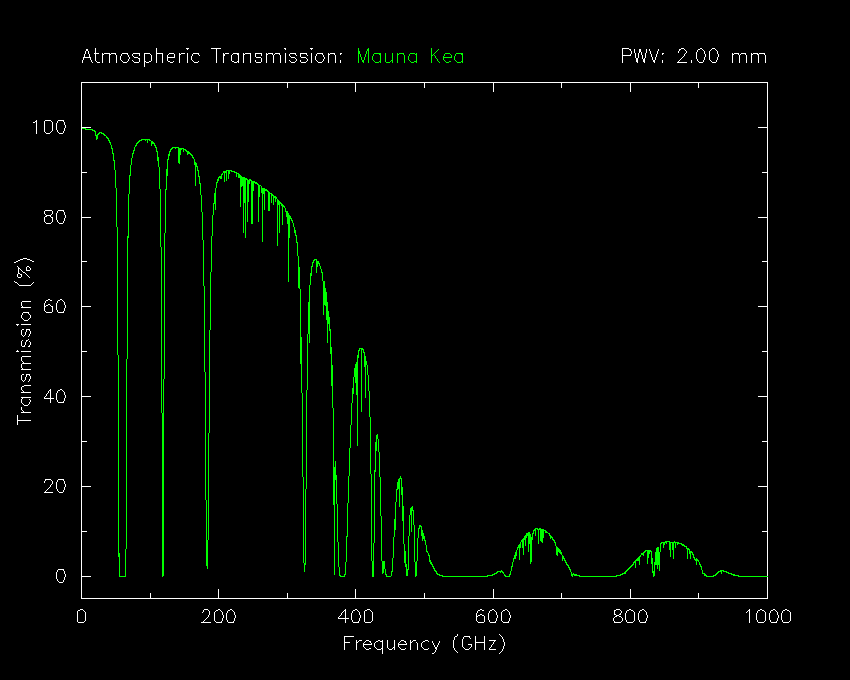

So let’s go microwave! For reasons that will become

clear later, we want the highest frequency (shortest wavelength) we can

get without losing too much in the atmosphere. Below is a plot generated

from an interactive tool associated with the Caltech Submillimeter

Observatory (where I had my first Mauna Kea observing experience). This

plot corresponds to a dry sky with only 2.0 mm of precipitable water

vapor. Even so, water takes its toll, absorbing/scattering the

high-frequency radiation so that the fraction transmitted through the

atmosphere is tiny. Only at frequencies of 100 GHz and below does the

atmosphere become nearly transparent.

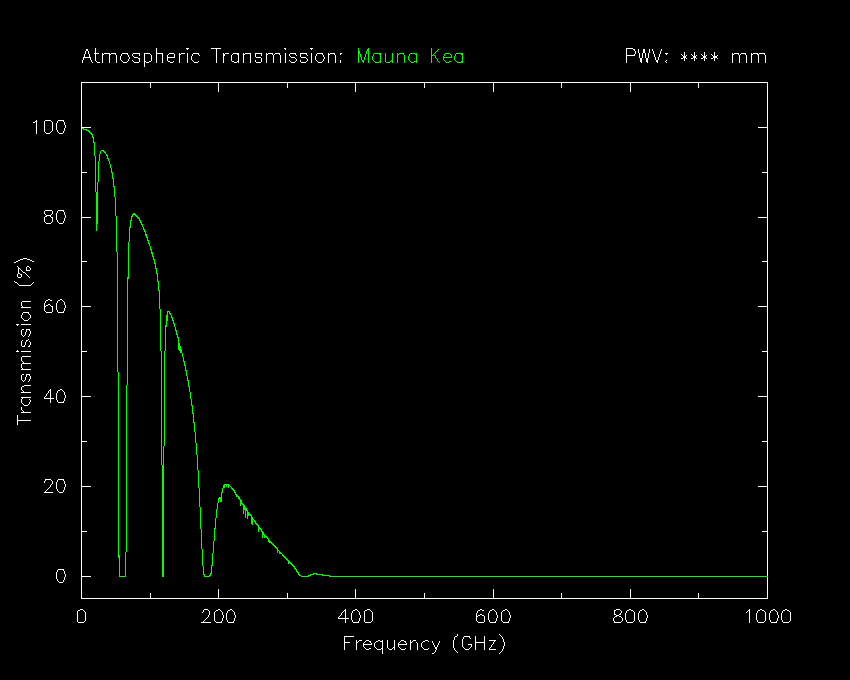

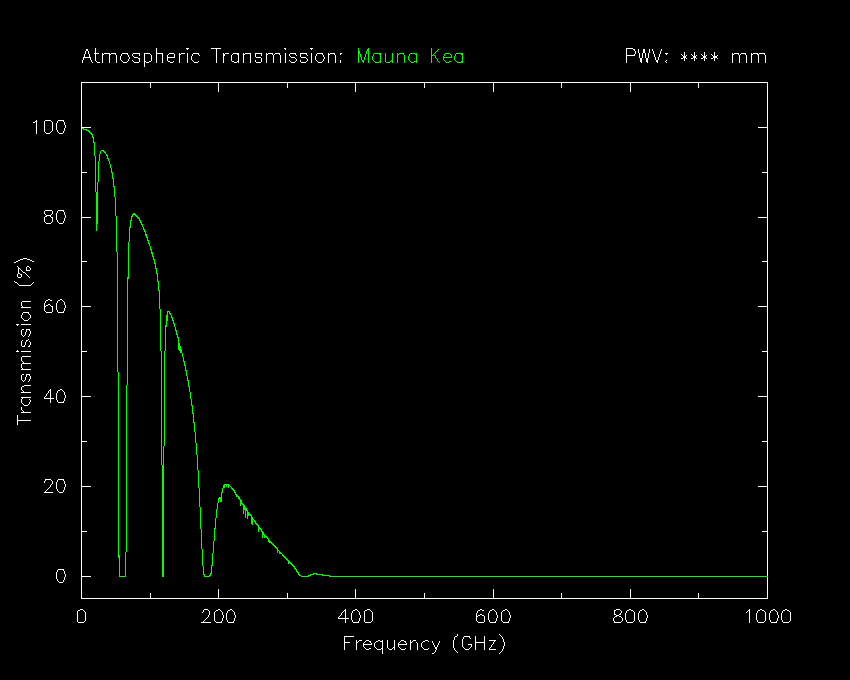

But if we have 25 mm of precipitable water (and

thick clouds have far more than this), we get the following picture,

which is already down to 75% transmission at 100 GHz. Our system is not

entirely immune to clouds and weather.

But we will go with 100 GHz and see what this gets

us. Note that even though microwave ovens use a much lower frequency of

2.45 GHz (λ = 122 mm), the same dielectric heating mechanism

operates at 100 GHz (peaking around 10 GHz). In order to evade both

water absorption and dielectric heating, we would have to drop the

frequency to the radio regime.

At 100 GHz, the wavelength is about λ ˜ 3 mm. In

order to transmit a microwave beam to the ground, one must contend with

the diffractive nature of electromagnetic radiation. If we formed a

perfectly collimated (parallel) beam of microwave energy from a dish in

space with diameter Ds—where the ‘s’ subscript represents the space

segment—we might naively anticipate the perfectly-formed beam to arrive

at Earth still fitting in a tidy diameter Ds. But no. Diffraction

imposes an angular spread of about λ/Ds radians, so that the beam

spreads to a diameter at the ground, Dg ˜ rλ/Ds, where r is the distance

between transmitter and receiver (about 36,000 km in our case). We can

rearrange this to say that the product of the diameters of the

transmitter and receiver dishes must approximately equal the product of

the propagation distance and the wavelength: DsDg ˜ rλ

So? Well, let’s first say that Ds and Dg are the

same. In this case, we would require the diameter of each dish to be 330

m. These are gigantic, especially in space. Note also that really we

need Dg = Ds + rλ/Ds to account for the original extent of the beam

before diffraction spreads it further. So really, the one on Earth would

be 660 m across.

Launching a microwave dish this large should strike

anyone as prohibitively difficult, so let’s scale back to a more

imaginable Ds = 30 m (still quite impressive), in which case our

ground-based receiver must be 3.6 km in diameter!

Now you can see why I wanted to keep the frequency

high, rather than dipping into the radio, where dishes would need only

get bigger in proportion to the wavelength.

Converting Back to Electrical Power

At microwave frequencies, it is straightforward to

directly rectify the oscillating electric field into direct current at

something like 85% efficiency. The generation of beamed microwave energy

in space, the capture of the energy at the ground, then conversion to

electrical current all take their toll, so that the end-to-end process

may be expected to have something in the neighborhood of 50% efficiency.

Beam Safety and Consequences

I don’t worry too much about keeping the beam from

veering off the collection region. There are clever, fail-safe schemes

for ensuring proper alignment/pointing. According to the Wikipedia page on

the topic, the recommended transmission strength would be 230 W/m² in

the center of the beam. This is about a quarter the strength of full

sunlight, and is thought to be a safe level through which aircraft and

birds can fly.

At this level, our 3.6 km diameter collecting area

would generate about 40 GWh of energy in a day, at an assumed

reception/conversion efficiency of 70%. By comparison, a flat array of

15%-efficient PV panels occupying the same area in the Mojave Desert

would generate about a fourth as much energy averaged over the year. So

these beaming hotspots are not terribly more concentrated than what the

sunlight provides already. Again, I find myself scratching my head as to

why we should go to so much trouble.

Launch Costs

This brings us to the tremendous cost of launching

stuff into space. Today’s cost for putting stuff into geosynchronous

orbit is about $20,000 per kilogram

of launched material. We have a history of hope and optimism that

launch costs will plummet in the future. So far, that has not really

happened, and rising energy prices are not going to help drive costs

ever-lower. Meanwhile, the U.S. space program appears to be scaling

back.

In 1999, NASA initiated a $22 million study

investigating the feasibility of space-based solar power. Among their

conclusions was that launch costs would need to come down to $100–200

per kg to make space-based solar power economically competitive. It is

hard to imagine accomplishing a factor-of-100 reduction in launch costs.

Let’s do our own quick analysis. A standard rooftop

panel delivers about 10 W per kilogram of mass (slightly better than

this, but I will stick to round numbers). Let’s say a light-weighted

version for space achieves an impressive factor-of-100 improvement: same

power for 1% the mass. This gives 1 kW/kg. I might be grossly

over-optimistic in this estimate, but we’ll see where it takes us.

Ignoring other infrastructure overhead (wiring, propulsion systems,

structural support, microwave transmission antenna, communications,

etc.), we end up with a launch cost of $40 per delivered Watt,

accounting for 50% delivery efficiency—and this is just the launch cost.

I’ll bet the space-qualified ultralight PV panels are not as cheap as

the knock-about panels we put on our roofs for $2/W. So maybe the cost

of the space hardware, launch of all systems, and build-out of expansive

ground systems will cost upwards of $60/W—becoming $400/W if we don’t

manage the 100× weight reduction per Watt, settling for 10× instead.

Granted, the constant illumination provides a factor of three in favor

of space, so we can give it a 3× discount for its full-time

contribution. But still, compared to typical ground installation costs

at $5/W, we find that the solar approach is at least four times more

expensive. You can even throw in batteries in the ground system without

exceeding the space cost, and all the reasons for going to space have

melted away.

Energy Return on Energy Invested

My initial reaction to the notion of flinging solar

panels in space was that the energy needed to launch panels to

geosynchronous orbit might totally undermine the energy delivered by

such a system. Let’s take a quick look with approximate numbers.

First, today’s silicon solar panels return their investment of energy after 3–4 years of deployment.

Stick them in the sun for 30–40 years, and you have an EROEI of 10:1.

Specially light-weighted space panels will likely require more energy to

make per kilowatt, but will spend a much greater fraction of their time

in space soaking up energy. Let’s just guess that the payback would be 5

years if the space panel were deployed on the ground. But in space, the

panel works five times longer per day than the panels for which the 3–4

year payback is calculated. So let’s call it an even one year for

manufacture payback in space. Panels in space will be subjected to a

much harsher cosmic ray (and damaging debris) environment than those on

the ground, so we should reduce the lifetime to, say, 20 years. Still,

that’s a 20:1 EROEI for the manufacturing piece alone. But then there’s

the launch.

A study of gross weight of rockets compared to

payload delivered to geosynchronous orbit reveals a roughly 100:1 ratio.

This intuitively makes sense to me given the logarithmic rocket equation: much of the fuel is spent lifting the fuel that must be spent to lift more fuel, etc. (see the appendix of the stranded resources post for my explanation of this).

There is a nice rule of thumb—highly approximate—that the embodied energy

in products is about the same as that of the equivalent mass of

gasoline, at about 40 MJ/kg. Aluminum production requires more, at 220

MJ/kg, but many materials are surprisingly close to this value (and fuel

will be right on the mark). A rocket will use a lot of aluminum, but

much more fuel. So we might go with a round number like 50 MJ per kg.

If I take my ultra-lightweight panel producing 1

kW/kg, I must launch 100 kg of rocket, at a cost of 5 GJ. A 1 kW panel

will deliver 0.5 kW to the end-user, after transmission/conversion

losses are considered. The 5 GJ launch price tag is then paid off in 107

seconds, or about one third of a year. Add the embodied energy of the

other components in space and on the ground, and I could easily believe

we get to a year payback—now bringing the total (manufacture plus

launch) to two years and an EROEI around 10:1. If my 100×

light-weighting proves to be unrealistic, and we can only realize a

factor of ten improvement over our rooftop panels, the solar panel

launch cost climbs to three years, so that adding other components

results in perhaps a 4:1 EROEI.

In the end, the EROEI is not as prohibitive as I

imagined: it’s not a net energy drain as I might have feared. But it’s

not obviously better than conventional solar either.

In Summary

I sense that people have a tendency to think space

is easy. We have lots of satellites, we’ve gone to the Moon (remember

that?!), we used to have a space shuttle program, and we have seen many

movies and television shows set in space. But space is a very

challenging environment, and it is extremely costly and difficult to

deliver things there. If you go to the Fed-Ex site to get delivery

costs, you immediately get hung up on not knowing the postal-code for

space. Once in space, failures cannot be serviced. The usual mitigation

strategy is redundancy, adding weight and cost. A space-based solar

power system might sound very cool and futuristic, and it may seem at

first blush an obvious answer to intermittency, but this comes at a big

cost. Among the possibly unanticipated challenges:

>> The gain over the a good location on the ground is only a factor of 3 (2.4× in summer, 4.2× in winter at 35° latitude).

>> It’s almost as hard to get energy back to the ground as it is to get the equipment into space in the first place.

>> The microwave link faces problems with transmission through the atmosphere, and also flirts with roasting ducks on the wing.

>> Diffraction of the downlink beam, together with energy density limits, means that very large areas of the ground still need to be dedicated to energy collection.

Traditional solar photovoltaics in good locations

can accomplish much the same for much reduced cost, and with only a few

times more land than the microwave link approach would demand. The

installations will be serviceable and will last longer. Batteries seem

an easier way to cover storage shortcomings than launching stuff to

space. I did not even address solar thermal schemes in this post, which competes well with photovoltaics and can very naturally build in storage capability.

I am left puzzled as to why we would want to take a

harder, more expensive road to solar power. I think it is just not

intuitive to most how difficult and expensive space is. And perhaps they

think it’s very futuristic and cool to push our power generation out to

space: it fits the preferred narrative about where we’re going. I don’t

know—I’m just guessing.

Astronomers frequently face this issue: should we

build a telescope/observatory on the ground, or launch something into

space? The prevailing wisdom is that if the science can be accomplished

on the ground, then by golly you’d best do it that way. You’ll have the

result sooner, at less expense, and with a greater chance of success.

The lion’s share of astronomical advance is carried out from the ground.

Space is reserved for those places where there is no other way. The

atmosphere blocks many interesting wavelengths, creates turbulence that

makes high-resolution imaging difficult, and produces variations in

transmission that make it impossible to measure fluxes to high

precision. The rotating Earth gets in the way of continuous observation

of a single target for long periods. Some of the more exciting (an

well-publicized) discoveries come from space missions, because these

avenues are not generally available to us, increasing discovery

potential.

Space-based solar power contains little intrinsic

advantage that we can get “only from space.” It looks like a wash at

best, and the astronomers would say “don’t bother.”

Tom Murphy is an associate

professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego. An

amateur astronomer in high school, physics major at Georgia Tech, and

PhD student in physics at Caltech, Murphy has spent decades reveling in

the study of astrophysics. He currently leads a project to test General

Relativity by bouncing laser pulses off of the reflectors left on the

Moon by the Apollo astronauts, achieving one-millimeter range precision.

Murphy’s keen interest in energy topics began with his teaching a

course on energy and the environment for non-science majors at UCSD.

Motivated by the unprecedented challenges we face, he has applied his

instrumentation skills to exploring alternative energy and associated

measurement schemes. Following his natural instincts to educate, Murphy

is eager to get people thinking about the quantitatively convincing case

that our pursuit of an ever-bigger scale of life faces gigantic

challenges and carries significant risks.

No comments:

Post a Comment